|

Today is an exciting day - I have finally managed to get my hands on some of the new Springbank Local Barley! Now, I must admit, my expectations are fairly (unreasonably?) high for this one as one of my favourite drams of all time is the 1966 Local Barley, which I first tried way back in 2003 at the Vienna Whisky Fair when the lovely chaps from the Austrian Whisky Society very kindly gave me a dram from their bottle in the bar after the show. I remember being absolutely blown away, not just by the whisky, but by the fact that a group of people I had never met before that weekend would share such an old, rare whisky with me, just because they thought I would like it and be interested to try it.

Released this month, this is retailing at around £95 a bottle, although I have seen some bottles sell at auction (yes, already!) for more than double that. Which brings me on to a rant that I have now and again when the subject of escalating whisky prices comes up. As consumers, we often complain that whisky is too expensive, that prices just keep rising. Which is true, but look at it from the producers point of view. How annoying must it be to see someone (or many someones in this case) buy your bottles, not to drink and enjoy, but to immediately flip at auction, making themselves more money per bottle than both the producer and retailer combined? If the market is willing to pay that higher price, then it is totally understandable that the producer would want to increase their share of the profits to allow them to reinvest in the business.

Using this Springbank Local Barley as an example, if Springbank were to charge an extra £20 a bottle (equating to an increase of about £50 on the retail price I would think) they would net themselves an extra £180,000 on a limited release of 9000 bottles such as this one. That’s a whole lot of man hours or casks or tonnes of barley that they are missing out on. In a way then, I think it is quite admirable that Springbank are only charging £95 a bottle for their latest Local Barley Release. I never thought I’d see the day when I considered £95 quid a reasonable price for a bottle of 16yo whisky but considering the price they could be charging (at least if auctions are anything to go by) and the increased costs associated with the local barley releases (small batch, lower yield, higher production costs etc) I think they’re doing pretty well.

2 Comments

With France being such an important export market for scotch whisky (it’s been the biggest export market by volume for the last 10 years at least) there are many, particularly in the mainstream media, who, on reading such figures, would be wringing their hands in despair and proclaiming the end of the Scotch whisky industry as we know it.

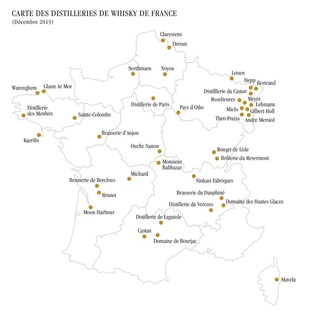

And that, dear readers, is what I want to discuss with you; the production methods, raw materials and history behind these numerous new distilleries in a country that I know extremely well as a scotch whisky export market, but have only a passing acquaintance with as a whisky producer in their own right. When you think about it, it shouldn’t really be surprising that the French are producing whisky. After all, they have just as long and illustrious a tradition of distilling as we do in Scotland, maybe longer. The first written record of distilling in Scotland dates back to 1494 when Friar John Corr bought 8 bolls of malt with which to distill acqua vitae. The first recipe for distilling wine in an alembic appeared as early as 1300. The French have been producing top class spirits for centuries; Cognac, Armagnac, Calvados. If anything, the question should be not, ‘why have they started producing whisky now?’ but ‘why did it take them so long?’. A recent article by Christine Lambert on slate.fr suggests that whisky was in fact produced in France some 300 years ago but the practice was lost in the mists of time because of an Icelandic volcano. Yes, you read that right. A volcano. Bear with me here. Apparently written records show that an ‘eau-de-vie made from grain, matured in wood’ (and if that’s not a description of whisky, I don’t know what is) was consumed at Stanislas’ Court in Lorraine in the mid-18th century. However, the volcanic ash clouds resulting from the eruption of the Laki volcano in Iceland in 1783 caused all sorts of meteorological chaos across Europe (particularly in France and the Netherlands) which in turn affected crops. A sort of rationing was put in place, and grain distillation was subsequently banned to preserve food stocks. Fruit distillation, however, was allowed to continue as it was a means of preserving the fruit. It does seem crazy that the eruption of an Icelandic volcano in the 18th century could perhaps have shaped an entire country’s distilling history but then, an Icelandic volcano also managed to ground the entire European aviation fleet for several weeks in the 21st century (and I should know, I was in Paris at the time and had a very, very long train journey back to the North of Scotland), so it’s maybe not that crazy.

Yes, French whisky is relatively new compared to Scotch, but they are not totally new kids on the block either. Ironically, at a time when age statements are disappearing from many scotch whiskies, they are just starting to appear on French ones. The first 10 yo French whisky came out in 2012 (Armorik) and the first 12yo in 2013 (Wambrechies). Philippe certainly thinks the future of French whisky looks rosy; “France has all the skills necessary to make her mark on the whisky market, both in France and abroad. In France because the French want to rediscover local products (locavore movement - Yep, I didn’t know what it was either but I googled it and apparently a locavore eats local, seasonal produce - Ed.) and today there is at least one distillery in each region of France. Since the terrorist attacks in 2015, they have become very proud of their country. (Bourbon sales exploded in the US after 9/11. It’s not a coincidence). Abroad thanks to the quality, luxury image that French wines and spirits already enjoy.”

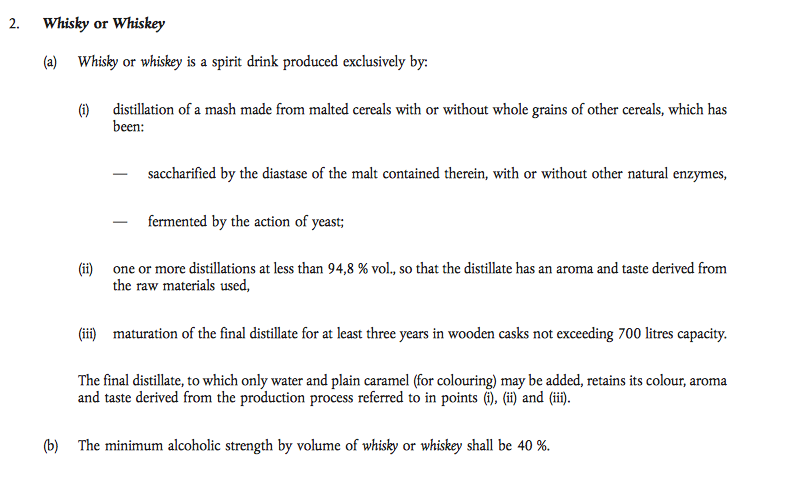

There are challenges ahead as well though. There are no big players and no one big blend brand so that means budgets are limited. (See, Diageo has its advantages - Ed.) Another potential problem is ‘fake’ French whisky. Since there is no legal definition, anyone could import grain spirit from Germany, India or Scotland, mature it in France and then sell it as French whisky.” The creation this month of the ‘Federation du Whisky de France’, a trade body similar in scope to the Scotch Whisky Association, will hopefully help to protect and build the reputation of true ‘Made in France’ whisky though. Certainly where food and drink are concerned my experience is that when the French do something they do it well so I, for one, am very excited to see what the future will hold for their many different whiskies. We may have to wait a wee while til we see a ‘French Whisky’ shelf in our local booze shop here in Scotland, but until then, I will just have to content myself with a spot of whisky tourism next time I’m in France (if there’s a distillery in every region, I shouldn’t be too far away from one, no matter where I go on holiday!). As to whether the Scots should be worried, I’ll leave the final word to Philippe; “Brandy is made all over the planet but everyone knows that the best brandies are French with Cognac and Armagnac. It’s the same for sparkling wines - they’re made everywhere in the world, but the best is Champagne. Today the best whisky is Scotch. And that’s great. French whisky just wants to be that little bit better. Like we’ve done with Cognac and Champagne. Give us a bit of time!” …I think he’s joking. Cheeky Frenchman! |

AuthorWhisky Impressions is run by Kate Watt. Previously at Springbank and then Glenfarclas, I now design some whisky related stuff and write about it, and anything else that takes my fancy, on this blog. Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed