|

I seem to have been writing about J & A Mitchell quite a lot recently, but since last weekend marked the 12th Anniversary of the opening (re-opening?) of Mitchell’s Glengyle distillery, I figured that warranted another post. At least it is about Kilkerran this time rather than Springbank!

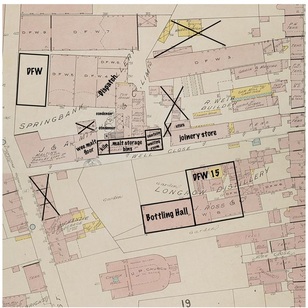

At the time, it was quite a novelty - it was one of the forerunners in the wave (now practically a tsunami) of new Scottish Distilleries, and the first distillery to open in Campbeltown in well over 100 years. The original Glengyle distillery had been founded in 1872 by William Mitchell, who ran it until 1919, when it was sold. It closed its doors a few years later in 1925. Although all the distilling equipment was removed, and the stock sold off, the distillery buildings themselves remained pretty much intact over the intervening years, being used first as a rifle range, then as an agricultural depot. The story goes that Mr Hedley G Wright, current chairman of J & A Mitchell Co Ltd, during one of his visits to Springbank, had noticed that the buildings were for sale and commented, “Hmm, my great-great uncle used to own Glengyle. I think I should buy it.” I may be paraphrasing slightly but you get the idea! Buy it he did (in November 2000), and the ambitious plan to create a brand new distillery within the walls of the old one began. The first time I saw the soon to be new Glengyle distillery, in 2002, it was an empty shell. A very large empty shell! Over the next couple of years though, I, along with all the other staff at Springbank, gradually watched the new distillery come to life under the direction of Mr Wright and Frank McHardy, who was Springbank Distillery Manager at the time. The stills and mill were sourced second hand - the stills from Ben Wyvis distillery and the mill from Craigellachie - although the shape of the stills was altered somewhat to give the distillery character they wanted. The rest of the equipment was new though - the very large stainless steel mash tun was brought down by road (I’d have hated to be stuck behind that lorry on the way down to the town!) and fitted by Forsyths of Speyside. I vividly remember watching the washbacks be built on site - now that was impressive! If you’ve ever been to a cooperage and watched them building casks, it was like that but on a much, much larger scale. The noise of 5 or 6 guys hammering the huge hoops into place around the newly installed washbacks was something else! I also remember the first time the new washbacks were filled - and the water just poured out the bottom! They do that apparently, until the giant staves absorb enough water to expand into place and make them watertight. That’ll be why they were filled with water first then, won’t it? (That’s also why wooden washbacks are kept full of water when not in use, so that they don’t dry out and start leaking).

4 Comments

It’s all the more remarkable then to think that at one point in time, Springbank was considered to be at the forefront of innovation and modernisation! In an article that Hedley G Wright, the current Chairman of Springbank, wrote for The Wine and Spirit Trade Record in 1963, he stated, “Springbank Distillery today has changed in several features from olden times. The company has been one of the pioneers of mechanisation within the distilling industry and the movement of barley and malt is now performed entirely by belts screws and elevators…The actual maltings have been rationalised so that there is only one set of floors and one kiln where formerly there had been two independent maltings…The green malt is dried on a pressure kiln of modern design and this item of equipment has been found to give a superior quality of malt and also effect considerable economy of time and fuel"

Then fermentation, “The actual washbacks are made of Scottish ‘boat-skin’ larch wood, for it is the belief of the proprietors that a steel wash back, although less expensive to install and maintain, gives a distinct taint to the final whisky, in an analogous manner to the distinctive tone given to a violin by the use of steel strings.” Then distillation, “The wash is pumped into a large copper still which is heated by a coal fire underneath and also, simultaneously, by an internal steam coil through which superheated steam is passed. This method of heating a wash still is the traditional Campbeltown technique and has been used at Springbank for as long as records indicate; it is thought that no distilleries outside Campbeltown use this method.”

Happily, all our fears were unfounded. We had a good turnout of around 60 people - some whisky enthusiasts, some novices and some that didn’t even like whisky but had come along because Rhona asked them to and it was for a good cause - We even managed to convert one of our non-whisky drinking friends! (Yes, we do have some!) The joint tasting thing seemed to go okay too, at least after the first dram or two, and, between ticket sales and the raffle, we raised a fantastic £1640 for Macmillan. All in all, a pretty successful evening. We had a pretty good tasting line up too thanks to Mark’s current employer, Cadenheads, and my previous employers, Springbank and Glenfarclas, who very generously donated all of the whisky for the event.

Huge thanks to everyone that provided whisky, raffle prizes and came along to support the event. Who knows, we may even do more joint tastings in the future!

Today is an exciting day - I have finally managed to get my hands on some of the new Springbank Local Barley! Now, I must admit, my expectations are fairly (unreasonably?) high for this one as one of my favourite drams of all time is the 1966 Local Barley, which I first tried way back in 2003 at the Vienna Whisky Fair when the lovely chaps from the Austrian Whisky Society very kindly gave me a dram from their bottle in the bar after the show. I remember being absolutely blown away, not just by the whisky, but by the fact that a group of people I had never met before that weekend would share such an old, rare whisky with me, just because they thought I would like it and be interested to try it.

Released this month, this is retailing at around £95 a bottle, although I have seen some bottles sell at auction (yes, already!) for more than double that. Which brings me on to a rant that I have now and again when the subject of escalating whisky prices comes up. As consumers, we often complain that whisky is too expensive, that prices just keep rising. Which is true, but look at it from the producers point of view. How annoying must it be to see someone (or many someones in this case) buy your bottles, not to drink and enjoy, but to immediately flip at auction, making themselves more money per bottle than both the producer and retailer combined? If the market is willing to pay that higher price, then it is totally understandable that the producer would want to increase their share of the profits to allow them to reinvest in the business.

Using this Springbank Local Barley as an example, if Springbank were to charge an extra £20 a bottle (equating to an increase of about £50 on the retail price I would think) they would net themselves an extra £180,000 on a limited release of 9000 bottles such as this one. That’s a whole lot of man hours or casks or tonnes of barley that they are missing out on. In a way then, I think it is quite admirable that Springbank are only charging £95 a bottle for their latest Local Barley Release. I never thought I’d see the day when I considered £95 quid a reasonable price for a bottle of 16yo whisky but considering the price they could be charging (at least if auctions are anything to go by) and the increased costs associated with the local barley releases (small batch, lower yield, higher production costs etc) I think they’re doing pretty well. |

AuthorWhisky Impressions is run by Kate Watt. Previously at Springbank and then Glenfarclas, I now design some whisky related stuff and write about it, and anything else that takes my fancy, on this blog. Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed